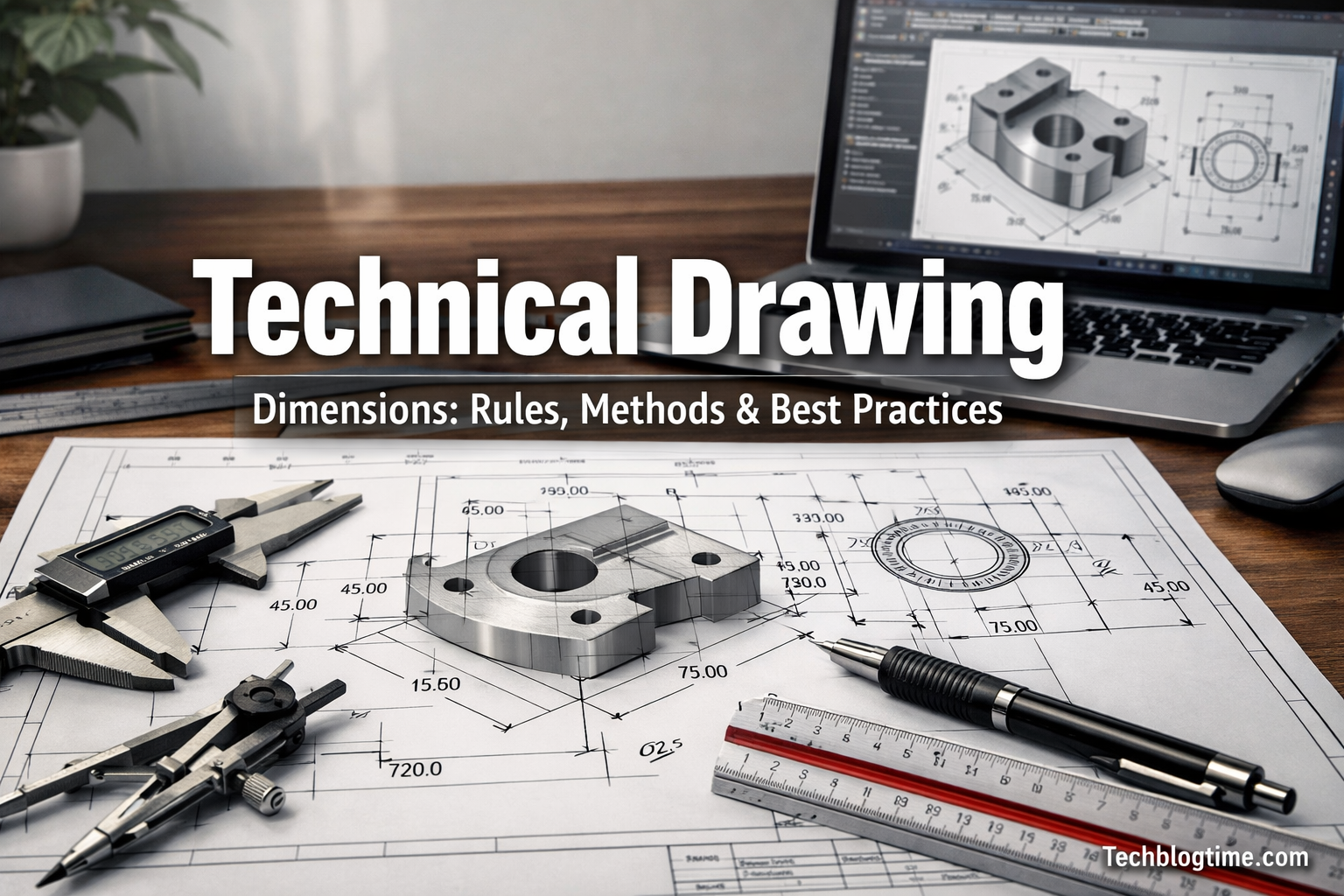

Technical drawing is the language of engineering, construction, and manufacturing. It transforms an idea into something that can be built, installed, inspected, and maintained. Among all elements of a drawing, dimensions are the most critical because they define the exact size, location, and relationship between features. A beautiful drawing without proper dimensions is useless in the real world. Even a minor dimensioning mistake can cause misalignment in mechanical parts, errors in fabrication, incorrect site installation, material waste, project delays, and costly rework. That is why learning dimensioning rules, methods, and best practices is not just important—it is essential for anyone working in drafting, engineering design, architecture, or MEP systems.

In this article, we will cover everything you need to understand and apply technical drawing dimensions correctly. Whether you are a student, a beginner draftsman, or a working professional wanting to improve your drawings, this guide will help you dimension like a true expert.

What Technical Drawing Dimensions Really Mean and Why They Matter

Dimensions in technical drawing are not simply numbers written on paper. They are official manufacturing and construction instructions. A dimension tells the reader exactly how big a part is, where a feature is located, and what limits are acceptable. In most industries, a technical drawing becomes a legal document between the designer and the manufacturer. This means that the dimensions must communicate design intent clearly, without ambiguity. If a drawing does not include correct dimensions, the operator or fabricator has to guess. And guesswork has no place in engineering.

Dimensions also control functionality. A hole in a plate is not just “a hole.” Its diameter and location determine whether a bolt will fit, whether a shaft will rotate properly, whether a flange aligns with another component, or whether a motor coupling works smoothly. In construction and MEP works, dimensioning affects everything from duct alignment to pipe routing, cable tray spacing, and equipment layout. Incorrect dimensions can lead to mismatched fittings, clashes, and structural conflicts.

Another reason dimensioning matters is inspection and quality control. When a component is produced, inspectors measure it against the dimensions on the drawing. If the drawing is unclear or incorrect, inspection becomes unreliable. In professional practice, dimensioning is not optional—it is the foundation of accuracy, standardization, and real-world implementation.

Fundamental Rules of Dimensioning in Technical Drawing

Technical drawing follows universal standards so that any trained engineer or technician can interpret drawings anywhere in the world. These standards ensure uniformity and reduce confusion. Although dimensioning styles may vary slightly between ISO and ANSI standards, the general rules remain the same.

The first essential rule is clarity. Every dimension should be readable, unambiguous, and placed in a way that does not overcrowd the drawing. Dimensions should not overlap, cross unnecessarily, or make interpretation difficult. The second rule is completeness. The drawing should contain all necessary dimensions for manufacturing or construction without requiring the reader to calculate missing values.

The third important rule is avoid duplication. A dimension should not be repeated in another view unless necessary. Repeated dimensions can create conflicts if updates are made in one place and forgotten in another. This often leads to serious errors in revision control. Another key rule is that dimensions must not be taken from the drawing scale using measurements. The drawing should clearly state: “Do not scale drawing.” The actual numbers are the real information.

A common professional rule is dimension from one datum or reference point. Random dimensioning leads to accumulated errors. By dimensioning from a common reference, tolerances can be controlled more effectively. Also, dimensions should generally be placed outside the object outline whenever possible, because internal dimensions reduce readability and increase clutter.

Finally, always ensure correct placement of dimension elements: extension lines should not touch the object directly, arrowheads must be consistent, and dimension lines should be clear. Good dimensioning is clean, structured, and systematic.

Types of Dimensions Used in Technical Drawings

To dimension properly, you must understand the major types of dimensions used across disciplines. Each type serves a different purpose and communicates a different design requirement.

Linear dimensions are the most common. They represent straight-line distances, such as length, width, height, thickness, depth, and spacing between features. Linear dimensions are used heavily in mechanical parts, structural elements, and architectural layouts.

Angular dimensions are used when features are inclined or rotated, such as chamfers, slopes, pipe angles, brackets, or mechanical linkages. Angular dimensions are always measured in degrees, and they must be placed clearly so that the angle’s arms are obvious.

Radial and diameter dimensions are used for circular features like holes, shafts, cylinders, arcs, fillets, and round edges. A diameter is represented using the symbol Ø, while radius is indicated with R. These symbols are standard and should never be skipped because confusion between radius and diameter can cause serious production mistakes.

Coordinate dimensions are often used in CNC machining or high-accuracy industries. Instead of dimensioning by chains, the position of holes or features is defined by X and Y coordinates from a datum. This is extremely useful when multiple features are placed in a pattern.

Limit dimensions define acceptable upper and lower limits. For example, a shaft diameter might be dimensioned as 20.00 ± 0.02 mm. This means the shaft can be between 19.98 and 20.02 mm. These dimensions are essential in precision assemblies.

In architectural and civil drawings, you may also see level dimensions, like floor height levels, pipe invert levels, or ceiling heights. These dimensions are vital because they define vertical positioning rather than just horizontal distance.

Dimensioning Methods: Chain, Baseline, and Coordinate Dimensioning

Dimensioning methods define how multiple dimensions are arranged and referenced. Choosing the correct method is a professional skill because it affects accuracy, tolerance buildup, and ease of reading.

Chain dimensioning is when dimensions are placed end-to-end like a chain. For example, if you have a plate with three holes spaced evenly, you might dimension hole 1 to hole 2, then hole 2 to hole 3. Chain dimensioning is simple and easy to apply, but it has a drawback: tolerance accumulation. If each distance has a tolerance, small variations add up across the chain, leading to large errors in total length or positioning.

Baseline dimensioning solves this issue by taking all dimensions from a single reference line. Instead of chaining, every hole is measured from the left edge, for example. This reduces tolerance buildup because each feature is controlled directly from the same datum. Baseline dimensioning is widely used in precision manufacturing, structural layouts, and MEP coordination.

Coordinate dimensioning is a more advanced method where positions are given as coordinates. This is common for CNC parts, sheet metal, and plate drilling patterns. The advantage is very clear position control and easy programming for machining. The drawing might include a table showing X and Y locations for each hole. Coordinate dimensioning also keeps the drawing clean because it replaces multiple dimension lines with a single table.

Choosing the right method depends on the application. For fabrication and general workshop work, chain dimensioning may be acceptable. For high accuracy assembly, baseline or coordinate dimensioning is preferred. A good draftsman knows when to switch methods for best results.

Placement and Formatting Rules for Technical Drawing Dimensions

Even if your dimensions are correct, poor placement can make the drawing confusing. The formatting rules exist to improve readability and reduce interpretation errors.

Dimensions should ideally be placed outside the object. This keeps the drawing uncluttered and makes lines easier to follow. If internal dimensioning is unavoidable, make sure it does not overlap with hidden lines, centerlines, or text. Proper spacing between dimension lines is also important. Crowding makes the drawing hard to read, especially when printed.

Another key rule is to maintain consistency in text height, arrow style, and units. Dimension text must be aligned properly and placed above the dimension line or within a break in the line. Arrowheads must be the same size across the entire drawing, and extension lines should have a small gap from the object outline.

Dimensions should never be placed on hidden lines. Hidden lines indicate features not visible in that view, and dimensioning on them creates confusion. Instead, choose another view or add a sectional view. If necessary, dimension the visible outline of the feature. For example, a hidden hole should be dimensioned in a section view or top view where it is visible.

The unit system must be clearly stated. In ISO drawings, millimeters are commonly assumed and may not be written with every dimension. In ANSI drawings, inches may be used. Regardless, the drawing should always specify units in the title block to avoid costly conversion mistakes.

Finally, avoid over-dimensioning. The purpose is not to fill the drawing with numbers, but to provide exactly what is needed to manufacture or install the object correctly.

Tolerances and Fits: Making Dimensions Realistic for Manufacturing

In the real world, no manufacturing process is perfect. That is why dimensions often include tolerances. A tolerance defines the acceptable variation in size. Without tolerance, every dimension would require impossible precision and would increase production cost significantly.

There are different types of tolerances in technical drawing. The most common is plus/minus tolerance, where a dimension is given with an allowable range. For example, 50 ± 0.5 means the part can be between 49.5 and 50.5. Another type is limit tolerance, where the upper and lower limits are written explicitly, such as 49.5 – 50.5.

In mechanical engineering, tolerances become extremely important in assembly fits. Fits determine how parts behave when assembled, such as a shaft inside a bearing. Common fit types include clearance fit, interference fit, and transition fit. If the tolerance is too loose, the assembly may wobble. If too tight, parts may not fit at all.

Manufacturers often prefer general tolerances for non-critical dimensions. These are provided in a note, such as: “Unless otherwise specified, tolerance ±0.1 mm.” This saves time and reduces drawing clutter. However, critical features must still be dimensioned with specific tolerances.

The best practice is to apply tolerance only where necessary. Over-tolerancing increases cost because it demands higher machining accuracy. A good engineer balances functionality with manufacturability. Dimensioning is not just about correctness—it is about practical production.

Common Technical Drawing Dimensioning Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced drafters can make errors, and dimensioning mistakes can have serious consequences. Understanding common mistakes helps you avoid them before the drawing reaches the workshop or construction site.

One of the most common mistakes is missing dimensions. If a drawing requires the fabricator to calculate something, the chance of error increases. Another frequent mistake is duplicate dimensions. If the same dimension is shown in multiple places, it can lead to conflicts during revisions.

Incorrect use of diameter and radius is also common. Writing “R10” instead of “Ø10” changes the meaning completely. Confusing radius and diameter can ruin a part instantly. Another mistake is dimensioning to hidden lines, which makes interpretation difficult.

A major professional problem is over-dimensioning. Adding unnecessary dimensions clutters the drawing and increases the chance of conflicting information. The purpose is to define manufacturing requirements, not to show every possible measurement.

Another critical error is poor tolerance planning. Some drawings show extremely tight tolerances everywhere, which makes production expensive. On the other hand, missing tolerances on critical features can cause assembly failure. Incorrect datum selection also causes cumulative errors, especially with chain dimensioning.

The best way to avoid these mistakes is to follow standards, use checklists, and review drawings carefully before release. In professional environments, drawings should always go through a verification process.

Best Practices for Dimensioning Mechanical and Engineering Drawings

Mechanical and engineering drawings require dimensioning that supports fabrication, machining, assembly, and inspection. Best practices help ensure drawings work in real production environments.

First, always dimension features according to function. For example, hole location is more critical than outside edge length in many parts. Dimension the functional features clearly and accurately. Second, use baseline dimensioning for features that must align precisely. This reduces tolerance buildup.

Third, provide enough views. A single view rarely contains all necessary information. Use orthographic projections properly: top view, front view, side view, and section views when required. Section views are essential for internal features like grooves, holes, threads, and cavities.

Fourth, dimension holes properly. Always specify diameter, depth (if blind), and whether it is through hole. If multiple holes exist, indicate the number and pattern. Example: “4x Ø10 THRU” indicates four holes, 10 mm diameter, through the material. Add countersink or counterbore details if needed.

Fifth, keep the drawing clean. Place dimensions systematically, group related dimensions together, and avoid crossing lines. A good drawing is easy to read even for someone seeing it for the first time.

Finally, include notes for machining processes if required, such as surface finish requirements, chamfer instructions, or welding symbols. Technical drawing is not just geometry—it is complete manufacturing communication.

Best Practices for Dimensioning Architectural, Civil, and MEP Drawings

In architectural, civil, and MEP drawings, the purpose of dimensioning shifts from manufacturing to construction and installation. Here, dimensions guide site teams, contractors, and supervisors. A wrong dimension can cause rework on a massive scale.

One of the best practices is to dimension from fixed building references such as grid lines, column centerlines, and structural walls. This ensures all trades align properly. In construction, baseline references are essential because the site relies on consistent coordinates and layout points.

Architectural drawings often use overall dimensions first, then internal dimensions. For example, a floor plan may show total building width, then room sizes, then openings like doors and windows. Civil drawings use chainage, levels, and offsets. MEP drawings use equipment clearances, pipe routing offsets, duct sizes, and installation elevations.

MEP dimensioning must consider accessibility and maintenance. For example, chillers, pumps, AHUs, and panels need service clearance. Dimensioning should help technicians understand spacing and accessibility, not just placement.

Also, coordination is vital. When multiple trades share the same space, dimensions help avoid clashes. Dimensioning in BIM environments must be clear and aligned with coordination standards. A professional drafter always checks for conflicts and ensures dimensions match real-world site constraints.

How to Improve Your Dimensioning Skills Like a Professional Draftsman

Dimensioning is a skill that improves with practice and observation. To become truly professional, you must go beyond software commands and understand engineering logic.

Start by studying standard drawings from real industries. Look at machine drawings, fabrication drawings, and construction shop drawings. Notice how dimensions are organized, what is included, and what is not. Learn to think like the person who will build the object.

Practice dimensioning the same part in different methods: chain, baseline, and coordinate. Understand how tolerance buildup works. Learn when to use section views and detail views. If you work in AutoCAD or Revit, focus on clean annotation style, consistent scale, and correct text height for printing.

Another important step is learning international standards like ISO and ANSI. Standards guide correct use of symbols, line types, and dimension formatting. In professional environments, standards compliance is mandatory.

Also, improve your checking habits. Before finalizing a drawing, ask yourself: Is every feature defined? Is there any unnecessary dimension? Can someone manufacture this part without asking questions? Are tolerances realistic? A professional drafter always checks their work as if money depends on it—because in real life, it does.

Finally, always aim for clarity. Technical drawing is communication. If your drawing is easy to understand, your dimensioning is successful.

Conclusion

Dimensioning is the backbone of every technical drawing. Without proper dimensions, even the most accurate sketch becomes incomplete and unusable. By following clear rules, applying the right dimensioning method, respecting standards, and using best practices, you can create drawings that are professional, reliable, and ready for real-world use. Whether you are working in mechanical engineering, manufacturing, architecture, or MEP design, mastering technical drawing dimensions will make your work more valuable, reduce errors, and improve your career growth.